Bullfighting: Traditions, Ethics, and Surprises

While bullfighting is a deeply cultural tradition in some parts of the world that dates back to ancient times, it has today become most closely associated with the countries of the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America, most notably Spain and a few of its former colonies like Mexico and Peru. The practice has also drawn a fair share of criticism and controversy in more recent times as activists and ethicists have raised increasingly public questions about the seeming barbarity of bullfighting in the modern era.

Some countries and even some regions of Spain have gone so far as to legally ban bullfighting, leading to the unprecedented intervention of Spain’s Constitutional Court on the grounds of “the preservation of common cultural heritage.” Whether you revere and enjoy bullfighting or detest the thought of it, it is important to understand its history as well as its modern reality in the context of a changing and globalized world.

Bullfighting is thought to have originated and spread throughout the Mediterranean provinces of ancient Greece and Rome more than 2000 years ago. Indeed it’s not hard to see how the well known ancient Roman spectacle of gladiators fighting animals and each other in arenas full of roaring crowds could have evolved into the highly choreographed art form that many see as the professional bullfighting shows of more recent centuries.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, these events continued to be staged in various forms by successive conquering powers. This was especially the case in the former Roman province of Hispania, which today corresponds mostly with the Iberian Peninsula of southwestern Europe, where the Visigoths continued the tradition of man vs. beast performances and where their conquerers, the Moors from northern Africa, evolved the tradition even further.

Accounts of these events during the 700-year Islamic period in Spain and Portugal show that the Moors preferred to fight the bulls on horseback while an array of assistants helped direct the bull around the arena with red capes. While the focus of the event in the territory that became Portugal has largely remained a man + horse vs. bull spectacle, with a particular emphasis on the skill of the horse as well as the horseman, bullfights in the areas re-conquered by the Castilians came to focus more on those facing down the bull on foot and the use of horses was eventually dispensed with.

Today bullfighting is strongly woven into the fabric of Spain’s cultural heritage. The form and format of modern bullfights in Spain can be traced to two of the country’s most famous bullfighters from the 18th century, Joaquín Rodríguez Costillares and Pedro Romero. Between the two of them, these legendary matadors popularized the techniques and equipment that have come to symbolize the art of bullfighting. These include the traditional matador costume, the sword, the cape, and the specific use of the cape for passes and the final kill.

While bullfighting is often called a sport, it is traditionally covered in the cultural sections of Spanish media. Fans and the industry judge a matador’s performance and skill on how smooth and suave he is in his movements, how close he gets the bull to his body, the bravery and indifference he shows to the danger posed by the ferocious animal (including often turning his back to the bull), and the artistic style he employs when finally killing the bull.

Although there are numerous examples of public opposition to bullfighting practices throughout history, including some members of the Catholic Church deeming it immoral at various times, bullfighting has survived and thrived largely thanks to it’s popularity with the Spanish people (so much so that even the Church backed down centuries ago) and its close association with Spanish identity and culture. But in more recent years, opposition to the practice has gained momentum.

Spain’s Canary Islands banned bullfighting as far back as 1991, but in 2010 Spain’s most prosperous region, Catalonia outlawed the tradition too despite it having previously been so popular that Catalonia largest city, Barcelona, had three bullrings alone. However, Spain’s central government in Madrid vowed to fight Catalonia’s ban and in 2016 Spain’s highest court intervened to invalidate the regional ban. This is still an ongoing political, cultural , and ethical issue in Spain and will surely continue to evolve.

Until now I have largely given an objective history of the tradition of Spanish bullfighting and touched on the opposition movement that has arisen and gained traction in recent years. But I have thus far avoided inserting my own opinion into the mix.

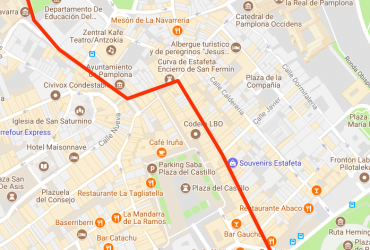

I have always known what goes on at a bullfight, including the fact that the bulls are killed at the end of the performance. However, it was not until I actually attended my first bullfight at Pamplona’s annual San Fermin Festival (which includes the Running of the Bulls) that I feel like I truly got a sense of what bullfights are actually like. And while the endless beer and sangria and the tens of thousands of exuberant fans in the stadium make for one hell of a party, my friends and I could only take watching the first four of six fights on the night we attended our first bullfight before we had to walk out and go home.

The term “bullfight” itself is a bit of a misnomer. The matador is indeed going up against the bull, but a severely wounded and crippled version of a bull, not a real bull in all its ferocious glory. In fact, I didn’t find much of anything glorious about “bullfighting” at all when I attended one. I had never really paid close attention before, but at the live event you can see that the bull has been heavily maimed before the “fight” even begins.

Before the matador begins his traditional show, the bull is impaled multiple times with long spears to weaken its strength. The bleeding animal is then run hither and tither around the arena to get its heart pumping and its blood flowing out of these puncture wounds. When the matador finally takes the stage, he uses the traditional cape to induce the wounded, frightened, and panicked animal into charging what it thinks is its predator until the bull is so exhausted and on death’s door that it can barely stand.

When the matador senses that the animal has nearly bled out and is on the verge of collapse from exhaustion, he moves in for the kill with his sword. While an excellent matador may be able to kill the bull in one fell swoop, all four of the bulls I saw fought in the one event I attended in Pamplona took multiple attempts to actually end the animal’s life. This was one of the most gruesome parts, the details of which I will spare readers.

After the bull finishes writhing and kicking on the floor of the arena and is clearly dead, a team of horses is brought out, ropes are tied around the dead bull, and it is ceremoniously dragged around the circumference of the arena as the crowd cheers wildly before the animal is finally taken back out of the same gate from which it had previously emerged alive 20 minutes before.

After seeing this spectacle repeated four times, my friends and I had had enough and decided to leave. It was then and there that I realized that what I’ve always known as a “bullfight” would be more accurately called an “animal torture show.” For this reason, I am now firmly in the anti-bullfighting camp on a personal level.

With all of that said, know that the bullfight is but only one small part of San Fermines. The Running of the Bulls every morning did not strike me as cruel or inhumane in the same way that the bullfights every evening did. But even excluding those two crowning events of each day, there are 22 more hours of jubilant festivities in which one can partake without anything to do with bulls.

So whether you hold the same opinion as I now do regarding bullfighting or whether you subscribe to the sentiment that it’s a necessary evil for the sake of preserving and celebrating a deeply rooted tradition, you can still have the time of your life enjoying San Fermines in Pamplona and the Running of the Bulls. Ole!